The Valuation Trap: Table of Contents

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Methodology

- Literature Review

- Theoretical Framework

- Analysis and Findings

- 6.1 The Power-Fear Nexus

- 6.2 Power as Human Need

- 6.3 Market Dominance and Power

- Discussion

- Conclusion

- Bibliography

Introduction

The nature of power has long been a subject of intrigue, particularly when considering how it is maintained. Power is a paradox: it relies on both attraction and exclusion, creation and scarcity. Whether in ancient religious institutions or modern market economies, the key to sustaining power lies in its ability to generate fear. Fear of exclusion, fear of loss, fear of being rendered powerless—these are the driving forces that ensure power structures remain intact. This book seeks to understand how power operates, how it thrives through fear, and how we can learn to navigate these systems.

The introduction sets the stage for a deeper dive into the interconnectedness of power and fear, and outlines the aims and structure of the book. We will explore historical case studies, psychological insights, and strategic frameworks to offer a comprehensive understanding of the dynamics at play in both personal and societal power systems.

Methodology

This novel blends philosophical analysis with case studies to uncover how power operates across various domains. By examining historical events, religious texts, market studies, and psychological research, we build a framework for understanding the underlying mechanisms of power. This approach will involve:

- Historical Analysis – Studying the evolution of power in different civilizations, from ancient Egypt to modern states.

- Religious Text Examination – Analyzing the role of fear and authority in religious structures and how it parallels modern systems.

- Case Studies of Power Transitions – Investigating shifts in power from one system to another, such as the rise of corporate giants or the fall of ancient empires.

- Psychological Research – Understanding the psychological foundations of power, particularly the role of fear, exclusion, and social hierarchy in maintaining power.

Literature Review

This section provides a summary of key theories related to power, fear, and human behavior, including classical power theory, evolutionary psychology, and market dynamics. We examine the works of key thinkers such as Max Weber, Michel Foucault, and contemporary scholars on market power and human psychology.

- Classical Power Theory – Weber’s three types of authority and their implications for understanding institutional power.

- Evolutionary Psychology – Insights into why humans seek power based on survival instincts.

- Market Power Studies – How businesses leverage scarcity and dependence to maintain dominance.

- Fear and Control – How fear is used across domains to enforce power and maintain hierarchies.

Theoretical Framework

The novel introduces the core concept of the Power-Fear Nexus as a framework for understanding power dynamics. Power, at its core, is maintained not only through the direct exercise of force but through the manipulation of fear. This section lays out the three main mechanisms that sustain power:

- Resource Control and Existential Fear – The role of scarcity and denial in the maintenance of power.

- Social Integration and Exclusion Fear – The psychological need for belonging and the threat of social exclusion.

- Physical Force and Bodily Fear – The ultimate use of violence or its threat to reinforce authority.

Analysis and Findings

6.1 The Power-Fear Nexus

This chapter explores the interdependence of power and fear. Historical and modern examples will demonstrate how the most enduring power structures operate on this dual mechanism. From ancient rulers who combined divine authority with brutal force to modern corporations that foster both attraction and exclusion, we’ll see how fear underpins every effective power structure.

6.2 Power as Human Need

Humans, by nature, seek power as a survival mechanism. This chapter delves into evolutionary psychology to explain why power is such a deeply ingrained need and how it translates into the formation of complex power structures. Yet, this need for power creates a paradox: to maintain its value, power must be tied to artificial scarcity.

6.3 Market Dominance and Power

Here, we explore how market leaders and corporations maintain their dominance not through isolation but through strategic positioning within larger networks. Small and medium enterprises (SMEs) that succeed in modern markets do so by creating dependencies, leveraging specialized knowledge, and cultivating relationships that create high switching costs.

Discussion

This section synthesizes the findings, reflecting on how power structures—religious, political, and economic—remain perpetuated through fear and exclusion. We will explore how understanding this dynamic can provide practical insights into how individuals can navigate, resist, or thrive within these systems.

Conclusion

The conclusion reflects on the key insights gained from examining the Power-Fear Nexus. It will discuss how this understanding not only enriches our view of historical and contemporary power systems but also offers practical tools for navigating these systems in the future. The book closes by offering strategies for transcending the limitations of self-referential human control systems, encouraging readers to consider how they can engage with or escape the trap of power and fear.

Bibliography

This section will list the key texts and research cited throughout the novel, including works by Max Weber, Michel Foucault, and modern scholars in evolutionary psychology, market power, and behavioral economics.

Chapter 1: The Power-Fear Nexus

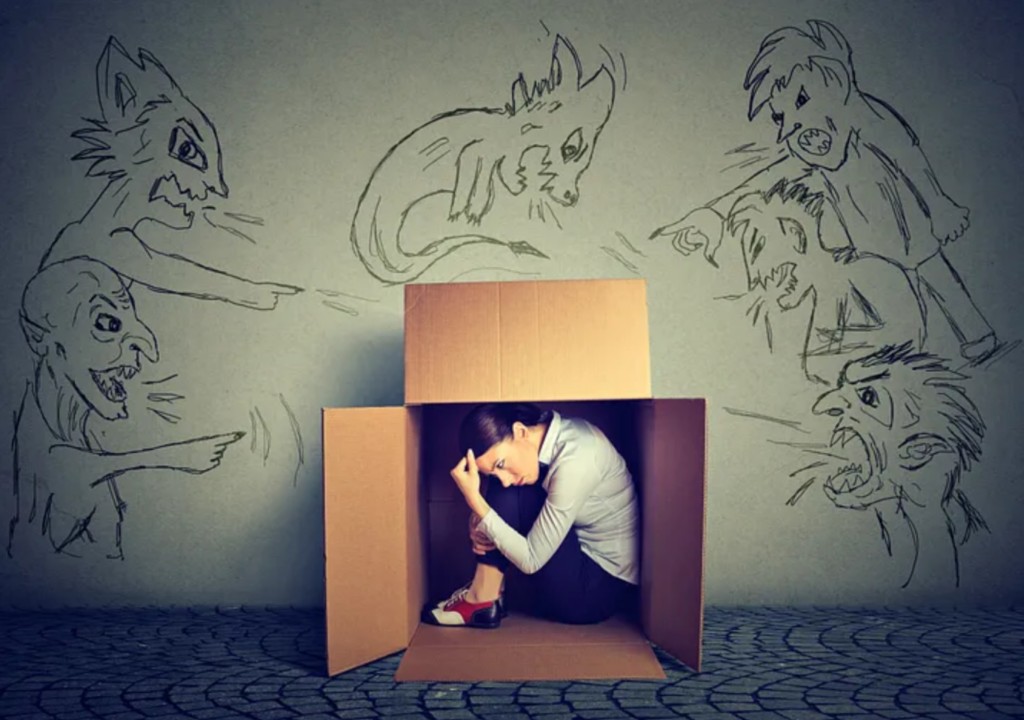

Power and fear are inextricably linked. This relationship defines every system of control throughout history and continues to shape modern societies. From the first rulers of ancient civilizations to the dominant global corporations of today, power exists not just because it attracts people, but because it induces fear—fear of scarcity, fear of exclusion, fear of loss. Without fear, power is weak. Without power, fear has no purpose.

The Power-Fear Nexus is a fundamental principle that underpins all human systems—whether political, social, economic, or spiritual. These systems rely on fear to perpetuate themselves and ensure their survival, even as they promise rewards, benefits, or salvation to those who comply. In ancient times, divine rulers combined the fear of punishment with the promise of salvation. In modern times, power manifests in more subtle forms, like economic dependence, social ostracism, and technological control.

The Mechanisms of Power

Power operates on a dual mechanism: it both attracts and excludes. At its core, power is about control—control over resources, information, and opportunities. This control is exerted through the promise of rewards for compliance and the threat of exclusion or punishment for defiance. A classic example is the way global tech companies, like Apple or Google, dominate the market not just by offering appealing products but by creating ecosystems that users feel they cannot easily escape. Once inside, users fear losing access to the services they depend on, which deepens their dependence on the brand.

In religious systems, this same dynamic is at play. Historically, religious leaders used divine authority to promise salvation, while simultaneously threatening damnation for those who deviated from the accepted norms. The fear of eternal punishment was as powerful a tool as the promise of eternal life, and together, they maintained a system of control that lasted for centuries.

In modern economic systems, fear is manufactured through financial dependence. Credit cards, loans, and mortgages create a cycle of debt where people fear economic instability or losing their wealth. Simultaneously, the promise of wealth and success through consumption and work keeps people engaged in the system.

The Evolution of Power Structures

Understanding how power evolved over time is crucial to recognizing its modern forms. In ancient societies, power was often centralized in the hands of a few individuals or families, and fear was wielded through direct control—whether through physical violence, sacrifices, or the threat of war. These systems were brutal but straightforward, and their mechanisms of control were visible.

Over time, power became institutionalized, and fear was no longer just a direct threat to one’s physical survival; it became embedded in societal norms and structures. Religious institutions, monarchies, and later, democracies, refined the methods of control. In the industrial age, power shifted into economic systems, where corporate entities replaced the divine and monarchical figures of the past. Fear, while still central to these systems, became more abstract: fear of poverty, fear of irrelevance, fear of failure.

In the digital age, power systems have become even more elusive. The most powerful companies—like Google, Facebook, and Amazon—do not control physical resources but control information, access, and connectivity. They generate fear by creating dependencies on their platforms, amplifying feelings of insecurity when users fear exclusion from their digital ecosystems. Fear of obsolescence or missing out on critical information drives engagement, ensuring these companies retain their dominance.

Fear as a Tool of Control

Fear is perhaps the most effective tool used to maintain power because it works on a subconscious level. It is not always a direct threat, but rather a constant presence, influencing decisions, shaping behaviors, and reinforcing the status quo. People are more likely to act in accordance with power structures when they fear the consequences of not doing so.

The psychological foundation of fear is rooted in our evolutionary biology. Fear of exclusion from the group was once a matter of life and death; in ancient societies, being cast out of the tribe meant certain death. This deep-seated fear of social exclusion is now leveraged by corporations, governments, and religious institutions to ensure compliance. The social media-driven society exemplifies this: the fear of being left out, of missing an important trend or development, keeps people engaged with platforms that shape their interactions and influence their opinions.

This fear extends beyond just exclusion; it encompasses the fear of loss. Losing one’s status, identity, or resources is often more compelling than the desire to gain them. This is why fear of losing a job is more motivating than the hope of a raise, why fear of public ridicule is stronger than the desire for validation, and why fear of financial collapse outweighs the promise of wealth.

The Paradox of Scarcity

Power thrives on the paradox of scarcity. For power to be valuable, it must be perceived as limited, something that can be lost or denied. Scarcity creates a sense of urgency, making the pursuit of power an ongoing, endless cycle. The illusion of scarcity is a cornerstone of modern economic systems—markets work because of perceived shortages, not actual shortages.

Consider the luxury goods market: brands like Louis Vuitton, Rolex, and others create artificial scarcity by limiting the availability of their products. This drives demand, as consumers fear missing out on something that is exclusive or rare. The same principle applies in the stock market, where scarcity is manipulated to create opportunities for those who understand the system.

In financial systems, scarcity manifests as limited access to credit, high-interest rates, or the creation of financial bubbles that promise wealth but ultimately lead to collapse. The economic cycles of boom and bust depend on the perception that wealth is limited and can be lost at any moment. This fear drives people to engage in risky investments, work longer hours, and sacrifice personal happiness for the chance to secure financial stability.

The Creation of Power Structures in the Digital Age

In the modern era, digital platforms have redefined how power and fear operate. Unlike traditional systems, which relied on tangible resources like land or military strength, digital platforms create power by controlling access to information and social interaction. The algorithmic control of social media platforms—where the ability to appear in someone’s feed is based on engagement metrics—creates a new form of fear: the fear of irrelevance.

People fear not only exclusion from society but from the conversation itself. Being left out of trending topics or missing out on viral moments can feel like social death in the modern age. This fear is intensified by the fact that digital platforms are often the primary source of social interaction, information, and entertainment. The more people fear being excluded, the more they conform to the algorithms that dictate what is seen and shared, creating a feedback loop that perpetuates the power of these platforms.

Chapter 2: The Fear of Freedom

Freedom is often hailed as the ultimate aspiration—the goal of liberation from oppression, control, and limitation. However, in reality, the pursuit of freedom is fraught with paradoxes and contradictions. While many long for the freedom to choose, act, and think independently, the true essence of freedom often reveals a deeper, more uncomfortable truth: it exposes individuals to responsibility, uncertainty, and even fear.

This fear of freedom is not merely a fear of the unknown or the uncertain; it is a profound psychological resistance to the weight of the choices freedom brings. This fear stems from an instinctual desire for security—an innate preference for the comfort of structure, order, and predictability. In a world where the systems that govern our lives are designed to control, predict, and manage behavior, freedom becomes a disruptive force, one that challenges the very essence of control.

The Burden of Choice

At the heart of freedom lies the burden of choice. To be free is to be responsible for one’s decisions, to bear the consequences of every action and inaction. While this might seem empowering, it also invites the fear of failure, judgment, and the unknown. The more choices we have, the more we are confronted with the possibility of making the wrong decision.

Modern societies are saturated with choice—from career paths to consumer goods, from political ideologies to social affiliations. While choice is ostensibly liberating, it often leads to paralysis. The abundance of options forces us to confront the overwhelming uncertainty of selecting the right path, making us question our values, desires, and priorities.

This fear is magnified by a cultural obsession with success, where the pressure to make the “right” choice can overshadow the joy of making an authentic, personal decision. Every decision becomes a potential mistake, every path a potential misstep that could lead to regret, social failure, or economic loss.

The Escape into Systems

In many ways, systems are designed to alleviate the fear of freedom. From governments to corporations, religions to social norms, systems provide structure, offering clear guidelines for behavior and the promise of stability. In exchange for conformity, individuals are promised security—security from fear, from failure, from the chaos of choice.

The human tendency to seek refuge in systems is deeply embedded in our psyche. Systems offer a comforting sense of predictability and order. They reduce the chaos of life into manageable categories, helping individuals navigate complex social landscapes with a semblance of clarity. In this sense, systems function as a psychological escape from the overwhelming weight of personal freedom.

While systems promise protection, they often come at the cost of personal autonomy. Conformity to a system means surrendering the freedom to think, act, and choose independently. In this way, systems act as both a comfort and a trap, offering safety from the chaos of freedom while simultaneously constraining the individual’s capacity to truly navigate their own life.

The Illusion of Control

An important facet of the fear of freedom is the illusion of control. While freedom presents the opportunity to direct one’s life according to personal will, it also brings the burden of uncontrollable outcomes. This reality induces anxiety, as the absence of control over external factors—be they financial, social, or environmental—leads to an overwhelming sense of vulnerability.

For most people, control over their environment or circumstances is a necessary condition for peace of mind. Systems of power, whether political, economic, or social, offer the illusion of control. In adhering to these systems, individuals convince themselves that their lives are governed by predictable rules and structures, reducing the uncertainty of their personal choices.

However, this perceived control is often illusory. The systems that promise stability often harbor contradictions and complexities that render them unpredictable. Economic recessions, political upheaval, and even technological disruptions expose the fragility of these systems, reminding individuals that true control is, in fact, unattainable.

The Desire for Certainty

Human beings crave certainty. Certainty provides a sense of security and reassurance in the face of life’s inherent unpredictability. It allows individuals to act with confidence, knowing that their choices will yield predictable outcomes. The fear of freedom, in part, arises from the absence of this certainty.

In modern society, this desire for certainty is often exploited by systems of control. Advertisements, political propaganda, and corporate messages all promise certainty in a world of instability. These promises—whether of financial security, political stability, or social approval—offer an illusion of control that appeals to the fearful, certainty-seeking psyche.

The systems of control that dominate our world thrive on this desire for certainty. By providing structures that appear stable and predictable, they attract individuals who long for security. However, this reliance on external systems for certainty ultimately inhibits personal growth and limits the capacity for genuine freedom. The more individuals look to these systems for reassurance, the less capable they become of handling the uncertainty of life on their own.

The Fear of Abandonment

Beneath the fear of freedom lies a deeper, often unspoken fear: the fear of abandonment. Freedom, by its very nature, can create a sense of isolation. The more individuals embrace personal autonomy, the more they risk being ostracized from the group, whether it be a social circle, community, or nation.

This fear of abandonment is particularly potent in social systems, where belonging is often equated with survival. Throughout history, groups and tribes have bonded over shared beliefs and practices, creating a sense of identity and collective security. To break away from these systems is to risk rejection, isolation, and disconnection from the group.

In modern societies, this fear is exacerbated by the rise of social media and the constant need for validation. In an age where public approval is a key measure of success, the idea of rejecting mainstream systems of thought and behavior becomes an act of self-doubt. The fear of abandonment in this context is not just a fear of physical isolation but a fear of being rendered irrelevant in a society that thrives on interconnectedness.

Navigating the Fear of Freedom

The fear of freedom is not easily overcome, but it is not insurmountable. To navigate this fear, individuals must learn to embrace uncertainty and relinquish the need for control. True freedom lies not in the certainty of systems but in the ability to act without fear of failure or judgment.

This requires cultivating an understanding of personal responsibility—the realization that freedom is not a void to be filled with external systems but a space to be filled with authentic choice. By accepting the responsibility that comes with freedom, individuals can begin to navigate the complexities of life with greater clarity and confidence.

Additionally, embracing the discomfort of uncertainty is key to overcoming the fear of freedom. Life, by its nature, is unpredictable, and the more we resist this truth, the more we are enslaved by the systems that promise stability. The fear of abandonment can be confronted by creating a sense of belonging within oneself, independent of external approval.

In this way, the fear of freedom becomes not an obstacle but an opportunity for growth. It forces individuals to confront the systems that control them and question the assumptions that govern their lives. Through this process, they can achieve a deeper, more meaningful freedom—one that is rooted in self-awareness, authenticity, and the courage to navigate the unknown.

Chapter 3: The Allure of Control

Throughout history, control has been the driving force behind the formation of societies, institutions, and power structures. While freedom promises the possibility of personal autonomy and individual growth, control offers something more immediate: security, predictability, and power. The allure of control lies in its ability to reduce the complexity of life into manageable structures, offering a sense of safety and order.

However, this allure comes at a significant cost. The pursuit of control—whether personal, political, or social—can lead to the suppression of freedom, the erosion of individuality, and the manipulation of reality. This chapter explores the nature of control, the systems that perpetuate it, and the ways in which individuals and societies become entangled in the quest to dominate and stabilize their environments.

The Desire for Stability

The core of the desire for control lies in the human craving for stability. Life is chaotic, unpredictable, and often harsh. In the face of uncertainty, humans are driven to seek out systems that offer a sense of predictability and order. Control becomes a way to shape the world according to specific needs, desires, and goals. It offers an illusion of mastery over one’s environment, allowing individuals and societies to mitigate risks and reduce uncertainty.

This desire for stability can be seen in the creation of institutions, governments, and systems of law. These structures are not simply mechanisms for governance; they are, at their core, tools for ensuring stability. By establishing clear rules, hierarchies, and regulations, control offers the promise of a predictable world where events unfold in a way that can be understood and anticipated.

However, the stability offered by control is often an illusion. While systems of control may offer short-term security, they are inherently fragile. They are susceptible to disruption, whether from internal failure or external forces. The more tightly control is held, the more rigid and brittle the system becomes, making it vulnerable to collapse in the face of unpredictable events.

Control and the Desire for Power

Power, in its most basic form, is the ability to shape outcomes and influence the behavior of others. Control is intimately linked to power, as it provides the means by which individuals and groups can impose their will on others and their environment. The allure of power is deeply ingrained in human nature, as it promises autonomy and the ability to dictate the course of events.

However, the desire for power is not merely a personal ambition; it is also a social and cultural force. Throughout history, power has been concentrated in the hands of those who control the means of production, communication, and governance. Those who possess control over these systems wield the power to shape the lives of others, to manipulate the flow of resources, and to influence the trajectory of societies.

This concentration of power is often justified by the notion that those who control the system are best equipped to maintain order and ensure the well-being of society. However, this argument is frequently a smokescreen for the perpetuation of inequality, exploitation, and manipulation. The systems that claim to offer stability and security often serve the interests of those in power, rather than the broader society.

The Mechanisms of Control

The mechanisms of control are diverse and multifaceted, ranging from psychological manipulation to physical coercion. While overt forms of control—such as dictatorship, surveillance, and military force—are readily apparent, more subtle forms of control are often even more pervasive and insidious. These forms of control operate through the manipulation of information, the shaping of public opinion, and the enforcement of social norms and expectations.

One of the most powerful mechanisms of control is the manipulation of fear. Fear is a primal emotion that triggers the fight-or-flight response, motivating individuals to act in ways that prioritize survival. Control systems exploit this fear by creating or exaggerating threats—whether real or imagined—in order to maintain power and influence. By stoking fear, those in control can rally people to their cause, suppress dissent, and justify repressive measures.

Another critical mechanism of control is the manipulation of language and discourse. Language shapes reality by framing how we perceive the world. Through control of language, those in power can define what is acceptable, what is possible, and what is true. Political rhetoric, media propaganda, and advertising all work to shape perceptions, reinforcing the status quo and discouraging critical thinking.

Social norms and expectations also function as mechanisms of control. From childhood, individuals are conditioned to conform to societal norms—whether related to behavior, appearance, or beliefs. These norms create a powerful sense of belonging and acceptance, but they also serve to suppress individuality and dissent. Those who deviate from the norm risk being ostracized or marginalized.

The Costs of Control

While control offers the promise of stability, security, and power, it comes at a significant cost. The more tightly control is maintained, the less room there is for personal freedom, creativity, and innovation. Control stifles the individuality of the people it seeks to govern, reducing them to mere cogs in the machine.

Furthermore, control perpetuates inequality. Those who are in positions of power often use their control to maintain their advantage, exploiting the resources and labor of others to further their own interests. The systems of control that perpetuate these inequalities are often disguised as benevolent or necessary, obscuring the true cost to those who are subjected to them.

Control also suppresses the potential for genuine growth and development. True innovation and progress arise from the freedom to explore, experiment, and challenge the status quo. Control, in contrast, discourages risk-taking and curiosity, as it prioritizes conformity and predictability over experimentation and exploration. In societies where control is paramount, new ideas are often met with resistance, and those who dare to challenge established norms are branded as troublemakers or dissenters.

The Paradox of Control: Freedom Through Submission

The most insidious aspect of control is the paradox it creates: the more people submit to control, the more they believe they are acting freely. In many systems, control is subtly embedded in everyday life, so much so that individuals often fail to recognize its influence. Social conditioning, cultural expectations, and political ideologies shape individuals’ perceptions of what is “normal” or “right,” making it difficult to distinguish between genuine freedom and the illusion of freedom.

This paradox is particularly evident in consumer society. Through advertising, social media, and cultural trends, individuals are encouraged to believe that their choices—what they buy, what they wear, who they associate with—are expressions of personal freedom. Yet, these choices are often preconditioned by external forces, subtly manipulating individuals into conforming to the desires and needs of corporations and social institutions.

The illusion of freedom through submission is also apparent in political systems. In many democracies, individuals are encouraged to believe that they have control over their lives through the act of voting. However, this form of participation often masks deeper systems of control, where political choices are shaped by money, power, and corporate influence. The act of voting may offer the illusion of freedom, but it often fails to address the underlying structures of control that shape political outcomes.

Breaking the Chains of Control

To break free from the allure of control, individuals must first recognize its presence in their lives. This requires a willingness to question the systems that govern them and to critically examine the beliefs and values they have internalized. It also requires a willingness to embrace uncertainty, chaos, and unpredictability—the very elements that control seeks to eliminate.

True freedom is not found in submission to external systems but in the cultivation of inner autonomy. This means embracing personal responsibility, rejecting the fear of failure, and acknowledging the limits of control. It means seeking authenticity and individuality, even when it means stepping outside the comfort of the status quo.

To navigate the complex web of control, individuals must learn to think independently, to act with intention, and to resist the pull of conformity. This involves reclaiming the freedom to choose and to shape one’s own destiny, rather than allowing external forces to dictate the course of life.

Breaking the chains of control is not an easy task. It requires courage, self-awareness, and a willingness to face the unknown. But in doing so, individuals can rediscover their true power—the power to shape their own lives, to create meaning, and to challenge the systems that seek to control them.

Chapter 4: Systems of Manipulation

As we continue to explore the nature of control, we must now turn our attention to the systems that perpetuate manipulation. While control operates through the mechanisms of fear, power, and regulation, manipulation works subtly beneath the surface, influencing behavior and perception in ways that are often invisible to those being affected. These systems—whether social, political, financial, or psychological—work to mold individuals and societies into obedient participants, often without their conscious awareness.

The systems of manipulation are far more insidious than overt forms of control. They infiltrate every facet of life, shaping beliefs, attitudes, and actions in ways that appear natural or even inevitable. Manipulation is not always the product of malice or ill intention; it can be the result of unconscious patterns, outdated ideologies, and societal norms that have become so deeply entrenched that their harmful effects go unnoticed.

The Foundations of Manipulation

At the heart of manipulation lies the ability to influence the way people think, feel, and act. This influence is rarely direct; it is often indirect, operating through channels such as media, education, and social interactions. Manipulation thrives in the gaps between what people perceive as reality and the underlying forces shaping that reality.

One of the most powerful tools of manipulation is the control of information. Information shapes understanding, and those who control the flow of information have the power to shape the way society perceives itself and the world around it. In modern times, the control of information has become more concentrated than ever before, with a few corporations, governments, and institutions controlling the vast majority of the narratives presented to the public.

Through selective reporting, spin, and omission, these powerful entities can shape perceptions, creating a narrative that aligns with their interests while suppressing dissenting viewpoints. The stories told through mainstream media, social media, and advertising shape collective consciousness, reinforcing particular beliefs and ideologies that serve the status quo.

The Psychology of Manipulation

Manipulation is also deeply embedded in human psychology. As social creatures, humans are naturally inclined to seek acceptance and approval from others. This desire for social validation can be used against individuals, as they are led to conform to societal expectations, even when those expectations conflict with their own desires or beliefs.

Psychological manipulation often works through the use of cognitive biases—systematic errors in thinking that influence judgment and decision-making. These biases can lead individuals to make decisions that are not in their best interest or to adopt beliefs that are not based on reason or evidence.

For example, the bandwagon effect is a cognitive bias that occurs when individuals adopt beliefs or behaviors simply because they are popular or widely accepted. This bias is often exploited in political campaigns, advertising, and social movements, where individuals are encouraged to align themselves with the majority in order to avoid social rejection or to feel part of a larger group.

Another powerful form of psychological manipulation is the use of authority. People are naturally inclined to defer to authority figures, whether they are parents, teachers, religious leaders, or political figures. By establishing themselves as authorities, those in power can influence the thoughts and actions of others, often with little resistance.

Economic Manipulation: The Invisible Hand

One of the most pervasive forms of manipulation is economic manipulation, which operates on a global scale and affects nearly every aspect of modern life. While economics is often portrayed as a neutral, scientific discipline, it is, in reality, deeply intertwined with power and control. The economic systems in place today are designed to maintain and perpetuate the power of the few, while keeping the masses in a perpetual state of dependence and insecurity.

The concept of the “invisible hand”—a metaphor used to describe the self-regulating nature of free markets—has been used to justify policies that benefit the wealthy and powerful. However, this metaphor overlooks the very real mechanisms of manipulation that govern economic systems. Economic policies, financial institutions, and corporate practices are often designed to concentrate wealth and power, leaving the majority of people struggling to keep up.

Corporations and financial institutions have an unparalleled ability to influence the economy. Through lobbying, campaign donations, and media influence, they can shape policy decisions to their advantage, ensuring that the system works in their favor. Meanwhile, the general public is left to contend with the consequences of economic inequality, job insecurity, and rising living costs.

Economic manipulation is also fueled by consumerism—the relentless drive to consume more, spend more, and accumulate wealth. Advertising, marketing, and social media create a culture of desire, where individuals are encouraged to define their worth by what they own rather than who they are. This culture perpetuates a cycle of consumption, debt, and dissatisfaction, ensuring that the economic system continues to function in favor of those at the top.

Political Manipulation: Shaping the Collective Will

Political systems, too, are deeply influenced by manipulation. While democracy is often hailed as the epitome of individual freedom and collective will, political manipulation operates behind the scenes, shaping the choices available to voters and ensuring that the system remains skewed in favor of the powerful.

The manipulation of the political process begins with the creation of narratives that shape public opinion. Political campaigns, media outlets, and interest groups all work to frame issues in a way that benefits their agenda. By controlling the narrative, these entities can influence how people vote, what policies they support, and which candidates they favor.

In many democracies, political manipulation operates through the use of money. Campaign financing, lobbying, and the influence of corporate interests all work to shape political outcomes. The result is a system where the interests of the wealthy and powerful are prioritized over the needs and desires of the general population.

Political manipulation is also evident in the ways in which elections are structured. Voter suppression, gerrymandering, and the control of voting districts all serve to dilute the power of certain groups while concentrating power in the hands of others. These practices undermine the democratic process, ensuring that the political system remains rigged in favor of those with the most resources.

Social Manipulation: Conforming to Norms

Social manipulation is perhaps the most subtle and pervasive form of manipulation. It operates through the establishment and enforcement of social norms—unwritten rules that govern behavior, interactions, and expectations. These norms are deeply embedded in culture and society, shaping how people think, act, and relate to one another.

Social manipulation often operates through the use of peer pressure. Individuals are influenced by the expectations of those around them, leading them to conform to group norms, even when these norms are harmful or limiting. The desire for social acceptance is so strong that people will often suppress their true selves in order to fit in with the group.

In addition to peer pressure, social manipulation operates through the control of identity. People are encouraged to define themselves in terms of external labels—such as race, gender, class, and nationality—which serve to reinforce divisions and perpetuate inequality. The systems that create and reinforce these labels operate subtly, shaping individuals’ sense of self-worth and limiting their potential.

Breaking Free from Manipulation

Breaking free from manipulation requires a deep awareness of the forces at play. It requires the ability to see through the narratives that are presented to us, to question the beliefs and norms that shape our lives, and to recognize when our choices are being influenced by external forces.

One of the first steps in breaking free from manipulation is to cultivate critical thinking. This means questioning the information presented to us, seeking out alternative perspectives, and being willing to challenge the status quo. Critical thinking empowers individuals to see beyond the surface and recognize the underlying systems of manipulation that shape their lives.

Another crucial step is to reclaim personal agency. This means taking responsibility for one’s own actions, choices, and beliefs, rather than allowing external forces to dictate them. By becoming more aware of the ways in which we are manipulated, we can begin to make more intentional decisions and create a life that is more authentic and aligned with our true values.

Finally, breaking free from manipulation requires the courage to resist conformity. It means rejecting the pressures to fit in, to follow the crowd, and to conform to societal expectations. True freedom comes from embracing individuality, authenticity, and the willingness to challenge the systems that seek to control and manipulate us.

Chapter 5: Manufactured Crises – The Strategy of Urgency

Control systems do not merely respond to crises—they manufacture them. The manipulation of urgency is one of the most effective tools used to consolidate power, override resistance, and reshape society. Whether economic collapses, wars, pandemics, or cultural upheavals, crises are strategically engineered—or opportunistically exploited—to justify extraordinary measures that would be unacceptable under normal conditions.

This chapter unpacks the anatomy of manufactured crises: how they’re constructed, the psychological mechanisms they trigger, and the strategic advantages they offer those in power.

Crisis as Catalyst

In every system of power, change is difficult to implement without resistance. Populations are naturally wary of major shifts, especially those that restrict freedom or require sacrifice. A crisis provides the perfect pretext—a moral imperative—to suspend normal rules and accelerate drastic transformation.

Leaders understand this well. As Rahm Emanuel once put it, “Never let a serious crisis go to waste.” This doesn’t imply every crisis is fake—but rather that real or artificial, crises are tools. They allow governments, corporations, and institutions to bypass debate, implement sweeping policies, and install new control mechanisms while the public is distracted by fear and urgency.

This is not conspiracy—it is strategy. It is how systems adapt, consolidate, and evolve.

The Architecture of Crisis Creation

A manufactured crisis is rarely built from nothing—it is often an exaggeration or misdirection of real events. The process usually follows a predictable pattern:

- Pre-Conditioning the Mindset

Before the crisis unfolds, a narrative is seeded through media, think tanks, and policy forums. This narrative primes the public psyche, building anticipation and identifying the “problem” that must eventually be solved. - Trigger Event

A catalytic event—whether organic or staged—ignites the crisis. This may be a terrorist attack, a viral outbreak, a financial crash, or a sudden war. The specifics matter less than the psychological effect: fear, confusion, and disorientation. - Media Amplification

The media, often aligned with power interests, heightens panic through saturation coverage, emotional framing, and selective reporting. Dissenting voices are marginalized or censored. Information becomes one-dimensional, locking public perception into a narrow window of acceptable thought. - Moral Framing

The crisis is quickly moralized. You’re either with the solution or against public safety, unity, progress, or justice. This binary framing shuts down nuance, debate, or alternative perspectives. - Emergency Measures

Under the cover of urgency, emergency laws, surveillance expansions, economic policies, or social restrictions are introduced. These are portrayed as temporary, but they often become permanent fixtures. - Post-Crisis Institutionalization

Once the public adapts to the new normal, the temporary becomes institutional. Powers are not rolled back. Instead, they’re normalized, woven into the fabric of governance, economics, and culture.

Case Studies in Control Through Crisis

Let us explore a few examples—not to assert singular truths, but to illuminate patterns of systemic behavior.

- The War on Terror

After 9/11, fear reshaped the Western world. The Patriot Act, mass surveillance, indefinite detention, foreign invasions—all justified by the need for security. Yet, the long-term effects included the erosion of civil liberties, endless war, and a vastly expanded intelligence apparatus. The question remains: Was the reaction proportionate, or strategically excessive? - Financial Collapses

In 2008, the global financial system nearly imploded. But instead of restructuring predatory financial models, governments bailed out the architects of the crisis while burdening the public. Economic suffering was privatized before the crash, socialized after it. Meanwhile, wealth concentration intensified. - Pandemic Policies

The COVID-19 pandemic revealed how rapidly fear can justify sweeping restrictions on movement, speech, and bodily autonomy. While the virus posed genuine risks, the response raised deeper questions: Who decides what counts as “misinformation”? How much control can be taken in the name of safety? And once that control is normalized, how easily is it relinquished?

These examples are not accusations—they are reflections of a larger pattern: crises as control levers.

The Psychology of Fear and Obedience

At the core of crisis manipulation is fear. Fear suppresses critical thinking. It narrows the scope of attention, making people easier to direct. In a crisis, the desire for order often outweighs the desire for truth. This is why crises are never just about events—they’re about perceptions.

Authority becomes a beacon in chaos. People seek strong leaders, experts, and institutions for guidance. This instinct is human—but exploitable. If the system itself created the chaos, the solution it offers may not be in the public’s best interest.

This psychological vulnerability is not inherently evil—it’s part of our design. But it must be counterbalanced by awareness. Otherwise, we become tools in the hands of those who wield manufactured urgency.

Strategic Benefits of Manufactured Crises

Why do power systems return to crisis again and again? Because crises:

- Unify compliance: In fear, populations behave more predictably.

- Accelerate policy: Controversial changes can be rushed in under emergency conditions.

- Weaken resistance: Protests, opposition, and legal barriers become delegitimized or criminalized.

- Legitimize surveillance: Control becomes a “necessary protection.”

- Reset economic systems: Old debts and failed models are wiped clean, while wealth consolidates upward.

- Expand globalism or nationalism: Depending on which serves the agenda, crises push integration or division.

The result is a world in permanent emergency mode—a society always on the edge, never quite allowed to return to equilibrium.

The Manufactured Loop: Crisis, Reform, Crisis

What’s most dangerous about this pattern is its cyclical nature. Manufactured crises are not anomalies; they are engineered resets. Each loop:

- Establishes control.

- Allows a brief illusion of reform.

- Then destabilizes again—by design or by mismanagement.

People get hopeful during the “reform” phases—new leaders, new narratives, new technologies—but the cycle always loops back to another emergency. This loop conditions the public to accept control as the cost of survival.

Breaking the Cycle: Strategic Awareness

To escape this loop, we must stop reacting to crises as purely external events. Instead, we must ask:

- Who benefits from this crisis?

- What narratives are being suppressed?

- What permanent changes are being implemented under the guise of urgency?

- Are the “solutions” proportionate, or pre-planned?

We must become analysts, not just participants.

This doesn’t mean denying real danger. It means refusing to give away agency out of panic. It means demanding transparency, refusing binary narratives, and cultivating resilience—psychological, economic, and informational.

Conclusion: The Crisis Mirror

Every crisis, real or manufactured, reveals something about the system—and something about ourselves. Our willingness to surrender, our desire for certainty, our susceptibility to fear—all come to the surface.

But these moments also offer opportunities: to see the machinery of control exposed, to strengthen our discernment, and to organize our lives around deeper principles than safety or conformity.

Because a crisis cannot be manufactured in a truly sovereign mind. It may shake the world—but it cannot define the self.

Chapter 6: Modern Control Mechanisms

As the machinery of systemic power evolves, so too do its tools. No longer reliant solely on brute force or visible authority, modern control mechanisms operate subtly, seamlessly integrated into daily life. They do not demand obedience through violence—they manufacture consent through convenience, distraction, data, and engineered dependence.

Where ancient empires used swords, and colonial regimes used flags, modern systems use screens, algorithms, financial dependencies, and psychological programming. The control is cleaner. Quieter. But no less complete.

The Shift from Force to Framework

In earlier eras, power systems relied on external domination: visible hierarchies, military occupation, overt censorship. Compliance was enforced through threat.

But modern societies are more complex. Open coercion is inefficient and unstable. Instead, control has migrated inward—into the structure of incentives, the flow of information, and the architecture of belief.

Today, the most effective systems make people want their own confinement. They trade freedom for perceived comfort, security, and identity. This is the genius of modern control: the cage is internalized.

Mechanism 1: Digital Surveillance and Predictive Control

The internet, once hailed as a liberating force, has become a surveillance machine. Every click, search, purchase, and pause is data. This data feeds algorithms that predict, manipulate, and shape behavior in real time.

Social media platforms are not merely mirrors of society—they are engineers of it. They direct attention, enforce norms, suppress dissent, and reward compliance through visibility.

Modern surveillance isn’t about watching—it’s about shaping. If a system can predict your behavior, it can influence your choices before you’re even aware you’re making them.

This is preemptive control—more efficient than force.

Mechanism 2: Financial Leverage and Debt Dependency

Finance is no longer just a means of exchange—it is a tool of behavioral governance.

- Credit scores determine access to opportunity.

- Inflation erodes savings while inflating asset bubbles that favor the elite.

- Debt chains entire nations and populations to external decision-makers.

The individual lives paycheck to paycheck. The business survives on loans. The nation borrows to stay afloat. In such a system, freedom becomes conditional. Say the wrong thing, and you lose your bank access. Protest the wrong policy, and your crowdfunding gets cut.

Money is not just power. It is permission.

Mechanism 3: Psychological Programming and Identity Capture

Perhaps the most insidious mechanism is the one that operates in the mind.

From education to entertainment, modern systems shape not just what people think—but how they think. Critical faculties are dulled. Emotional triggers are heightened. Complexity is replaced by slogans. Questions are replaced by identities.

The modern human is conditioned to:

- Conflate disagreement with threat.

- Seek validation over truth.

- Attach their identity to ideologies they did not choose.

This is identity capture: the process by which individuals internalize narratives that make them more manageable, predictable, and aligned with system interests. Once your sense of self is linked to a label, you can be controlled by what that label is allowed to mean.

Mechanism 4: Cultural Saturation and Attention Control

Control requires attention. And attention, in the modern world, is fragmented by design.

The endless scroll, the dopamine loops, the crisis news cycle, the influencer distractions—they all serve one purpose: to exhaust the mind and dilute awareness. If people are too busy reacting, comparing, consuming, or chasing status, they won’t organize. They won’t reflect. They won’t question.

In such an environment:

- Depth is replaced by novelty.

- Purpose is replaced by performance.

- Wisdom is replaced by content.

This saturation keeps the population busy but powerless—filled with noise, empty of direction.

Mechanism 5: Algorithmic Governance and Soft Censorship

Modern censorship is not about banning books. It is about manipulating visibility.

You are not stopped from speaking—but your words are buried. You are not silenced—but your audience is restricted. You are not imprisoned—but you are digitally erased.

Algorithms determine which ideas live and which die. They do so without debate, due process, or accountability. And because they operate invisibly, the illusion of freedom is maintained.

This is soft censorship: control without confrontation.

Mechanism 6: Systemic Incentives and Career Capture

Even those who see the flaws in the system are often captured by it.

The scientist who questions consensus risks funding. The journalist who reports the unsanctioned truth loses access. The academic who deviates from orthodoxy is professionally isolated. The entrepreneur who refuses compliance loses platform privileges.

The system does not need to jail dissidents—it simply denies them participation. This form of control is quiet, effective, and cloaked in bureaucratic neutrality.

The Integration of Mechanisms: A Seamless System

These mechanisms do not operate in isolation. They are interlinked, reinforcing each other:

- Surveillance feeds algorithms.

- Algorithms shape beliefs.

- Beliefs justify economic policies.

- Economic dependence enforces silence.

- Silence maintains the illusion of consent.

This seamless integration creates a system where resistance feels both futile and invisible. The individual may sense something is wrong—but struggles to identify where the control lies, or how to exit it.

Control Without a Face: Decentralized Power

One of the most powerful aspects of modern control is its decentralization.

There is no singular dictator. No throne to overthrow. No building to storm.

Control is embedded in systems, codes, norms, and networks. It is diffused across platforms, agencies, corporations, and AI. This diffusion makes it resilient—and harder to blame. When no one is responsible, no one can be held accountable.

This is the age of faceless power.

Can Control Be Good?

Some will argue these systems are necessary: to keep order, to fight misinformation, to optimize society. And indeed, not all control is malicious. Infrastructure, law, health, and safety require coordination.

The question is not whether systems should exist—but who designs them, who benefits from them, and whether individuals can opt out.

In a truly free society, systems serve the individual. In a captured one, the individual serves the system.

Conclusion: Awareness as the First Escape

Control mechanisms evolve. They adapt. They hide.

But every mechanism has a vulnerability: exposure.

To name a mechanism is to weaken its hold. To see the pattern is to escape its hypnosis. Once aware, the individual regains leverage—the ability to choose, question, and redesign.

Control may be seamless. But so is insight.

Chapter 7: The Navigation Challenge

Once a system of control is exposed, a new question arises—not how it works, but how to move within it without being consumed or corrupted. Exposure is only the beginning. The real battle is navigation.

To see the trap is one thing. To move through it without being captured, co-opted, or crushed—that is the true art.

The Illusion of Binary Choices

One of the first navigation traps is false polarity. Systems of control are often structured around binary choices:

- Left vs. Right

- Capitalism vs. Communism

- Freedom vs. Security

- Compliance vs. Rebellion

But these choices are designed to trap. Both options are often system-generated. The real danger lies in believing that your only choices are the ones the system has given you.

To navigate well, one must ask: Who created the menu? And what lies off it?

Three Roads and Their Traps

There are typically three intuitive responses to systemic control—each with their own risks:

- Conform – Adapt to the system to gain comfort or safety. The trap: you become dependent on its validation and blind to its limits.

- Rebel – Reject the system aggressively. The trap: your rebellion is often predictable and easily contained or used to justify further control.

- Escape – Withdraw from the system. The trap: total isolation often leads to irrelevance or vulnerability, and rarely scales into influence.

Each has moments of usefulness, but none offer a full solution.

Real navigation is not about binary postures—it is about dynamic balance, situational awareness, and strategic positioning.

Strategic Awareness: The Map vs. The Terrain

To navigate a complex system, you must distinguish between:

- The Map: What the system tells you the world is.

- The Terrain: What the world actually is beneath the system’s framing.

Modern systems give us maps full of narratives, data, identities, and norms. But maps are never neutral—they are designed.

A true navigator tests the map against the terrain. They don’t just consume narratives—they trace their sources. They don’t just accept terms—they examine who benefits from the framing.

Navigation begins with this distinction.

Calibration: Knowing When to Comply, When to Resist

The skilled navigator does not oppose everything. Nor do they obey blindly. They calibrate.

- Invisibility: Sometimes, blending in gives you time and space to build strength.

- Visibility: Other times, strategic confrontation reshapes perception or inspires others.

- Silence: At moments, withholding truth preserves it.

- Speech: At others, speaking truth shakes the illusion.

Navigation is not about rigid principles—it is about fluid wisdom. Timing. Discernment. Precision.

Tool 1: Intellectual Sovereignty

To move freely, one must think freely.

This requires reclaiming the ability to reason independently from media cycles, institutional biases, or peer group pressures. It means mastering:

- Logic over emotion.

- Evidence over ideology.

- Depth over speed.

The sovereign mind asks: Is this true? What’s missing? What’s being incentivized?

This mental discipline is rare—but it is the first tool of the navigator.

Tool 2: Emotional Clarity

Modern control often bypasses reason and targets emotion.

Fear, outrage, desire, guilt—these are system levers. If you are emotionally reactive, you are predictable. If you are predictable, you are programmable.

Emotional clarity means being able to feel without being steered. It means knowing:

- Where your fears come from.

- Who benefits from your anger.

- When your hope is being harvested.

The navigator feels deeply—but does not get lost in the feeling.

Tool 3: Strategic Relationships

No one navigates alone. Alliances matter.

But in a controlled system, most networks are compromised—by incentives, fear, or ignorance. The navigator builds high-trust, low-visibility relationships: individuals or small groups who share values, see clearly, and operate with integrity.

These bonds are often decentralized, unannounced, and built over time. They are the roots beneath the surface—resilient and quietly powerful.

Tool 4: Multiple Interfaces

The system rewards single identities. “Be one thing, stay in one lane, declare your allegiance.” This makes you easier to categorize—and control.

The navigator resists this. They develop multiple interfaces:

- One for engaging the system.

- One for building alternatives.

- One for personal integrity.

This is not deception. It is design. You don’t fight a shapeshifting system by being one-dimensional. You fight it by being agile, layered, and adaptive.

Tool 5: Exit Strategies

Not all systems can be reformed. Some must be exited.

True navigation involves building or supporting parallel systems—in finance, communication, education, food, or governance. These parallel structures don’t need to be utopias. They only need to create options.

Power comes from having a choice. Control dies when exit is possible.

The Core Principle: Don’t Feed the System

Systems thrive on attention, fear, dependence, and division. Every time you:

- React predictably,

- Fight on its terms,

- Accept its framing,

- Need its validation—

You feed it.

The best navigation often involves strategic disengagement. Not out of apathy—but out of clarity. You stop being a player in its game and become a builder of your own.

The Inner Compass

Beyond all strategies lies one essential element: the inner compass.

Systems can fake truth, manipulate logic, fabricate identity. But they cannot replicate genuine insight, conscience, or alignment with a higher order.

Your compass is built through reflection, solitude, experience, and practice. It is the voice that says: This is right. That is real. This path, not that one.

In systems designed to confuse, your compass is your anchor.

Conclusion: The Navigator’s Paradox

To navigate a system is to engage it without becoming it. To touch corruption without being corrupted. To use tools without being used by them.

It is to move with both caution and courage, with both strategy and soul.

The navigator does not wait for systems to collapse. They move ahead of them. They walk with one foot inside the world that is—and one foot in the world that must be built.

Chapter 8: Beyond Human Systems

There comes a point in every journey of awareness when the question changes.

No longer is it “How do I survive within the system?”

But rather: Is the system the limit of reality?

What lies beyond human systems? What precedes them, what transcends them—and what inner power remains untouched by manipulation, incentive, or fear?

This chapter is not about escape into fantasy. It is about reconnection to original order. It is about rediscovering the patterns that control systems only imitate—and restoring your alignment with what cannot be corrupted.

The Limits of Human Design

All human systems, no matter how advanced, are:

- Self-referential

- Finite

- Prone to distortion over time

- Dependent on collective agreement

That includes governments, currencies, educational institutions, ideological movements—even technologies.

They are tools, not truths. But over time, they claim the authority of truth itself. They try to replace the divine, the eternal, the natural order.

When a human system tries to become god, it must manufacture:

- Absolute rules (in place of natural law)

- Manufactured awe (in place of reverence)

- Predictive control (in place of trust)

And yet, despite its reach, no system can ultimately control:

- A clear conscience

- A true connection

- An inspired mind

- A loving act

- A soul anchored in something higher

These are not system-generated. They come from beyond.

The Return to Pattern

There is a deeper pattern to reality—a source structure not invented by man, but inscribed into existence. You see it in:

- The symmetry of creation

- The embedded intelligence of the body

- The moral instinct of a child

- The mathematical harmony of the cosmos

- The arc of justice that returns, even if slowly

This pattern doesn’t demand control. It reveals order. It doesn’t enslave; it aligns.

Human systems mimic this pattern to gain legitimacy—but always fall short because they seek control, not coherence.

To move beyond systems is to align with the original pattern, not abandon order altogether.

Discerning the Corrupted from the Divine

To navigate truly, you must learn to distinguish between what is authentic and what is a simulation.

| Authentic Pattern | Corrupted System |

|---|---|

| Emerges organically | Enforced by threat |

| Respects free will | Demands obedience |

| Builds resilience | Creates dependence |

| Elevates the individual | Prioritizes the collective narrative |

| Seeks coherence | Seeks control |

| Invites responsibility | Assigns blame |

This discernment is spiritual, not just intellectual. It is felt as much as reasoned.

Transcendent Anchors

To live beyond human systems, you need anchors that do not move when the world shifts. These are not rules—but principles and postures:

- Integrity Over Image

What’s true when no one is watching? That is the real currency. - Connection Over Compliance

Systems demand compliance. But truth emerges in connection—with people, nature, the divine. - Silence Over Noise

In a world of endless stimuli, silence is subversive. It reveals what the system tries to drown out. - Surrender Over Striving

Not passive surrender to control—but active surrender to reality, to timing, to truth beyond your control.

Building the Pre-System Self

To live beyond systems, you must remember who you were before the system named you.

Before you were:

- A job title

- A political label

- A consumer

- A data point

- A social identity

You were: aware. Curious. Alive. Sovereign.

The work of liberation is not to become something new, but to shed what was added. To return to what is essential. Not naive—but whole.

Creating Parallel Realities

Beyond human systems doesn’t mean isolation. It means creating from a different source.

This is the birth of parallel realities:

- Relationships not based on utility, but mutual honor.

- Learning not based on conformity, but wonder.

- Economies not based on scarcity, but value creation.

- Communities not built on shared enemies, but shared vision.

These realities don’t replace the dominant system overnight—but they prefigure what’s next. They are seeds. Quiet revolutions.

The Humility of Mystery

There is a mystery beyond all systems, beyond even comprehension.

True freedom does not require total understanding. It requires humility before what is higher.

- The system wants certainty.

- The ego wants control.

- But the soul? It wants alignment.

To live beyond human systems is to walk in mystery—with trust, with discernment, with eyes open and heart intact.

Final Reflection

Human systems will rise and fall. They will continue to mutate, adapt, and seek control.

But you were not born to be a system product. You were born to be a pattern bearer—one who remembers, reflects, and realigns the world not through force, but by presence.

The path beyond human systems is not a rejection of humanity. It is a reclamation of it.

It is the return of the divine within the individual.

It is the rise of what cannot be programmed.

Epilogue: Beyond the Circle

At the center of every control system lies a loop—a circular logic that feeds itself:

- Fear creates obedience.

- Obedience sustains the system.

- The system manufactures more fear.

Round and round it goes.

To those inside, the circle feels infinite—inescapable. Its rules become reality. Its limits feel like law. Its definitions shape identity.

But every circle, no matter how tightly drawn, exists within a larger space.

And every soul, no matter how entangled, retains a point of origin outside the loop.

This is where your journey leads—not to a battle within the circle, but a departure from it.

The Exit Isn’t Loud

You may expect revolution. Fire. Collapse.

But exits from systems are rarely dramatic. They are quiet. Subtle. A shift in attention. A change in allegiance.

Not a breaking, but a turning.

- From fear to clarity.

- From validation to vision.

- From proving to presence.

- From reacting to remembering.

The world still spins. But you are no longer moved by it.

The Map Was Never the Territory

What you were shown was never the whole.

- The metrics didn’t measure value.

- The education didn’t teach wisdom.

- The laws didn’t uphold justice.

- The roles didn’t define your worth.

- The media didn’t reflect reality.

- The circle wasn’t the cosmos.

To step beyond the circle is to realize: the map is not the territory. The system is not the source. The words are not the experience.

Freedom doesn’t arrive when the world changes. It arrives when perception does.

What Is Left When the System Falls Silent?

Take away the incentives.

Take away the punishments.

Take away the audience.

Take away the agenda.

What remains?

- A still voice.

- A quiet knowing.

- A creative spark.

- A moral compass.

- A living presence.

- A soul, untouched.

That’s where your real life begins.

Your Role Now

You are not here to fix the system.

You are here to transcend it—and, by doing so, reveal a different way of being.

You are a pattern-holder. A builder of new orders. A reminder of what was forgotten. A seed of what is coming.

Live like it.

- Speak with clarity, even when the world is confused.

- Act with integrity, even when no one is watching.

- Love with strength, even when it’s inconvenient.

- Build what the system cannot imagine.

A Final Word

If you’ve made it here, you already know:

This isn’t just a book.

It’s a compass.

A signal.

A release.

You’ve seen how systems manipulate.

You’ve traced their corruption.

You’ve discerned the deeper patterns.

And you’ve remembered who you are.

Now go. Not with rage—but with revelation.

Not to destroy the world,

but to create one beyond it.